An observation that has been made many times is that the internet is a perfect place to disseminate mathematical knowledge that is worth disseminating but that is not conventionally publishable. Another observation that has been made many times is that either of the following features can render a piece of mathematics unpublishable, even if it could be useful to other mathematicians.

1. It is not original.

2. It does not lead anywhere conclusive.

A piece of unoriginal mathematical writing can be useful if it explains a known piece of mathematics in a new way (and “new” here does not mean radically original — just a slightly different slant that can potentially appeal to a different audience), or if it explains something that “all the experts know” but nobody has bothered to write down. And an inconclusive observation such as “This proof attempt looks promising at first, but the following construction suggests that it won’t work, though unfortunately I cannot actually prove a rigorous result along those lines,” can be very helpful to somebody else who is thinking about a problem.

I’m mentioning all this because I have recently spent a couple of weeks thinking about the cap-set problem, getting excited about an approach, realizing that it can’t work, and finally connecting these observations with conversations I have had in the past (in particular with Ben Green and Tom Sanders) in order to see that these thoughts are ones that are almost certainly familiar to several people. They ought to have been familiar to me too, but the fact is that they weren’t, so I’m writing this as a kind of time-saving device for anyone who wants to try their hand at the cap-set problem and who isn’t one of the handful of experts who will find everything that I write obvious.

Added a little later: this post has taken far longer to write than I expected, because I went on to realize that the realization that the approach couldn’t work was itself problematic. It is possible that some of what I write below is new after all, though that is not my main concern. (It seems to me that mathematicians sometimes pay too much attention to who was the first to make a relatively simple observation that is made with high probability by anybody sensible who thinks seriously about a given problem. The observations here are of that kind, though if any of them led to a proof then I suppose they might look better with hindsight.) The post has ended up as a general discussion of the problem with several loose ends. I hope that others may see how to tie some of them up and be prepared to share their thoughts. This may sound like the beginning of a Polymath project. I’m not sure whether it is, but discuss the possibility at the end of the post.

Statement of problem.

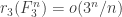

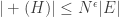

First, a quick reminder of what the cap-set problem is. A cap-set is a subset of that contains no line, or equivalently no three distinct points

such that

or equivalently no non-trivial arithmetic progression

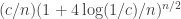

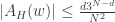

(Why it has this name I don’t know.) The problem is the obvious one: how large can a cap-set be? The best-known bound is obtained by a straightforward adaptation of Roth’s proof of his theorem about arithmetic progressions of length 3, as was observed by Meshulam. (In fact, the argument in

is significantly simpler than the argument in

which is part of the reason it is hard to improve.) The bound turns out to be

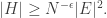

That is, the density you need,

is logarithmic in the cardinality of

This is why many people are interested in the problem of improving the bound for the cap-set problem: if one could, then there are standard techniques that often work for modifying the proof to obtain a bound for Roth’s theorem, and that bound would probably be better than

(at least if the improvement in the cap-set problem was reasonably substantial). And that would solve the first non-trivial case of Erdős’s conjecture that if

then

contains arithmetic progressions of all lengths.

If you Google “cap set problem” you will find other blog posts about it, including Terence Tao’s first (I think) blog post and various posts by Gil Kalai, of which this is a good introductory one.

Sketch of proof.

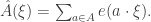

Next, here is a brief sketch of the Roth/Meshulam argument. I am giving it not so much for the benefit of people who have never seen it before, but because I shall need to refer to it. Recall that the Fourier transform of a function is defined by the formula

where is short for

stands for

and

is short for

Now

(Here stands for

since there are

solutions of

) By the convolution identity and the inversion formula, this is equal to

Now let be the characteristic function of a subset

of density

Then

Therefore, if

contains no solutions of

(apart from degenerate ones — I’ll ignore that slight qualification for the purposes of this sketch as it makes the argument slightly less neat without affecting its substance) we may deduce that

Now Parseval’s identity tells us that

from which it follows that

Recall that The function

is constant on each of the three hyperplanes

(here I interpret

as an element of

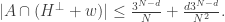

). From this it is easy to show that there is a hyperplane

such that

for some absolute constant

(If you can’t be bothered to do the calculation, the basic point to take away is that if

then there is a hyperplane perpendicular to

on which

has density at least

where

is an absolute constant. The converse holds too, though you recover the original bound for the Fourier coefficient only up to an absolute constant, so non-trivial Fourier coefficients and density increases on hyperplanes are essentially the same thing in this context.)

Thus, if contains no arithmetic progression of length 3, there is a hyperplane inside which the density of

is at least

If we iterate this argument

times, then we can double the (relative) density of

If we iterate it another

times, we can double it again, and so on. The number of iterations is at most

so by that time there must be an arithmetic progression of length 3. This tells us that we need lose only

dimensions, so for the argument to work we need

or equivalently

Can we do better at the first iteration?

There is a very obvious first question to ask if one is trying to improve this argument: is the first iteration best possible? That is, is a density increase from to

the best we can do if we are allowed to restrict to a hyperplane?

There is an annoying difficulty with this question, which is that the answer is trivially no if there do not exist sets of density that contain no arithmetic progressions. So initially it isn’t clear how we would prove that

is the best increase we can hope for.

There are two potential ways round this difficulty. One, which I shall adopt here, is to observe that all we actually used in the proof was the fact that So we can ask whether there are sets of density

that satisfy this condition and also the condition that

The other is to observe that a similar density increase can be obtained even if we look for solutions to

with

and

, where

and

are not assumed to be the same set. Now it becomes easy to avoid such solutions and keep the sets dense. If we do so, can we obtain a bigger density increase than the argument above (appropriately modified) gives? This again has become a question that makes sense.

The following simple example disposes of the first question. Let let

be a random subset of

of density

and let

be the set of all

such that their first

coordinates form a vector in

Then

has density

Let be the characteristic function of

Then it is not hard to prove that

unless

is supported in the first

coordinates. If this is the case, then as long as

the typical value of

is around

or around

It follows (despite the sloppiness of my argument) that

is around

If we could say that the typical value of was roughly its maximum value, then we would be done. This is true up to logarithmic factors, so this example is pretty close to what we want. If one wishes for more, then one can choose a set that is “better than random” in the sense that its Fourier coefficients are all as small as they can be. A set that will do the job is

(That sum is of course mod 3.) Again, the details are not too important. What matters is that there are sets with the “wrong number” of arithmetic progressions, such that we cannot increase their density by all that much by passing to a codimension-1 affine subspace of

Taking a bigger bite.

This is the point where I had one of those bursts of excitement that seems a bit embarrassing in retrospect when one realizes not only that it doesn’t work but also that other people would be surprised that you hadn’t realized that it didn’t work. But I’ve had enough of that kind of embarrassment not to mind a bit more. The little thought I had was that in the example above, even though there are no big density increases on codimension-1 subspaces, there is a huge density increase on a subspace of codimension Indeed, the density increases all the way to 1.

I quickly saw that that was too much to hope for in general. A different example that does something similar is to take a random subset of

(that is, with each element chosen with probability

), to take

to be the set of

with first

coordinates forming a vector in

and to let

be a random subset of

of density

(in

so each element of

is put into

with probability

). This set turns out to have a fairly similar size distribution for the squares and cubes of its Fourier coefficients, but now we cannot hope for a density increase to more than

even if we pass to a subspace of codimension

But that would be pretty good! We could iterate this process times and get to a density of 1, losing

dimensions each time. That would require

which would correspond to the best known lower bound for Roth’s theorem.

I won’t bore you with too much detail about the plans I started to devise for proving something like this. The rough idea was this: for each codimension- subspace

define

to be the averaging projection that takes

to

where

(The characteristic measure

of

is defined to be the unique function that is constant on

and zero outside

and that averages 1. The projection

takes

to

) Then I was trying expanding

in terms of its projections

It turns out that one can obtain expressions for the number of arithmetic progressions, and also a variant of Parseval’s identity. What I hoped to do was find a way to show that if we take

we can prove that there is some

such that

has order of magnitude

from which it follows straightforwardly that there is a density increase of order of magnitude

on some coset of

But how would such a result be proved? I had a few ideas about this, some of which I was getting pretty fond of, and as I thought about it I found myself being drawn inexorably towards an inequality of Chang.

Chang’s inequality.

It is noticeable that in the example that provoked this proof attempt, the large Fourier coefficients all occurred inside a low-dimensional subspace. Conversely, if that is the case, it is not too hard to prove that there is a nice large density increase on a small-codimensional subspace.

This suggests a line of attack: try to show that the only way that lots of Fourier coefficients can be large is if they all crowd together into a single subspace. A good enough result like that would enable one to drop down by more than one dimension, but not too many dimensions, and make a greater gain in density than is possible if one repeatedly drops down by one dimension and uses the best codimension-1 result at each step.

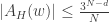

There is good news and bad news here. The good news is that there is a result of precisely this type due to Mei-Chu Chang: she shows that the large spectrum (that is, the set of such that

is large) cannot contain too large an independent set. (Actually, her result concerns so-called dissociated sets, but in the

context that means linearly independent.) The bad news is that the bound that comes out of her result does not yield any improvement to the bound for the cap-set problem: up to logarithmic factors, the number of linearly independent

for which

can have size

is around

, and even if we could somehow use that information to deduce that

has density 1 in a codimension-

subspace, we would end up proving a bound of

for the density needed to guarantee an arithmetic progression, which is considerably worse than one obtains from the much simpler Roth/Meshulam argument.

Let me briefly state (a slight simplification of) Chang’s inequality in the context. If

is a set of density

with characteristic function

then for any

the largest possible independent set of

such that

has size at most

For comparison, note that Parseval’s identity tells us that the number of with

cannot be more than

where

, which gives us a bound of

without the linear independence assumption.

Later we’ll think a little bit about the proof of Chang’s inequality, but first let us get a sense of how close or otherwise it comes to allowing us to improve on the bounds for the cap-set problem.

How might the structure of the large spectrum help us?

In this short section I will make a couple of very simple observations.

First of all, suppose that is a set of density

that contains no non-trivial arithmetic progression of length 3. Let

be the characteristic function of

Then as we have seen,

(That isn’t quite accurate, but it almost is, and it’s fine if we replace the bound by

say, which would not affect the arguments I am about to give.)

Now let us do a dyadic decomposition. For each positive integer let

be the set of all non-zero

such that

Then there are a few easy facts we can write down. First of all, by Parseval’s identity,

from which it follows that

Secondly, the contribution to the sum

from

such that

is, by Parseval again, at most

Thirdly, by the bound on the sum of the cubes of the Fourier coefficients, we have that

From this and the previous observation it follows that there exists such that

for some absolute constant

Thus, up to log factors (in ), there exists

such that the number of

with

is

This is a strengthening of the statement used by Roth/Meshulam, which is merely that there exists some

with

In combination with Chang’s theorem, and again being cavalier about log factors, this tells us that we have around values of

such that

and they all have to live in a subspace of dimension at most

So the obvious question now is this: can we somehow exploit the fact that the large spectrum lies inside some lowish-dimensional subspace?

A quick point to make here is that if all we want is some improvement to the Roth/Meshulam bound, then we can basically assume that since any larger value of

would allow us to drop a dimension in return for a larger density increase than the Roth/Meshulam argument obtains. However, let me stick with a general

for now.

If there are values of

all living in a

-dimensional subspace

such that

for each one, then

Therefore, the pointwise product of

with the characteristic function of

has

-norm squared equal to

It follows that the convolution of

with the characteristic measure of

, which is the function you get by replacing

by the averaging projection

of

defined earlier in this post, has

-norm squared equal to

Now never takes values less than

so the

-norm squared of the negative part of the projection of

is at most

Therefore, there must be some coset on which

averages at least

or so.

Thus, we can lose dimensions for a density gain of

Is that good? For comparison, if we lose just one dimension we gain

so losing

dimensions should gain us

Thus, the more complicated argument using the structure of the Fourier coefficients does worse than the much simpler Roth/Meshulam argument where you lose a dimension at a time.

When it is even easier to see just how unhelpful this approach is: to use it to make a density gain of

we have to lose

dimensions, whereas the Roth/Meshulam argument loses

dimensions in total.

Can Chang’s inequality be improved?

The next part of this post is a good example of how useful it can be to the research mathematician to remember slogans, even if those slogans are only half understood. For instance, as a result of discussions with Ben Green, I had the following two not wholly precise thoughts stored in my brain.

1. Chang’s inequality is best possible.

2. The analogue for finite fields of Ruzsa’s niveau sets is sets based on the sum (in ) of the coordinates.

The relevance of the second sentence to this discussion isn’t immediately clear, but the point is that Ben proved the first statement (suitably made precise) in this paper, and to do so he modified a remarkable construction of Ruzsa (which provides some very surprising counterexamples) of sets called niveau sets. So in order to come up with a set that has lots of large Fourier coefficients in linearly independent places, facts 1 and 2 suggest looking at sets built out of layers — that is, sets of the form where the sum is the sum in

and not the sum in

Incidentally, to the best of my knowledge, “fact” 2 is an insight due to Ben himself — no less valuable for not being a precise statement — though it is likely that others such as Ruzsa had thought of it too.

Let me switch to because it is slightly easier technically and I’m almost certain that whatever I say will carry over to

Let

be the set of all

such that

where

is an integer around

The density of this layer is about

for a positive absolute constant

Now let us think about its Fourier coefficients at the points

of the standard basis. By symmetry these will all be the same, so let us look just at the Fourier coefficient at

If we write

for the set of points

such that

then this is equal to the density of

minus the density of

The density of is half the density in

of the layer of points with coordinate sum

whereas the density of

is half the density in

of the layer with coordinate sum

So basically we need to know the difference in density of two consecutive layers of the cube when both layers are close to

The ratio of the binomial coefficients and

is approximately

or in our case around

Since the two densities are around

the difference is around

Thus, if we choose to be around

we have a set of density around

with around

Fourier coefficients of size around

Apart from the log factor, this is the Chang bound. (If we want a similar bound for a larger value of

then all we have to do is take a product of this example with

for some

)

Is this kind of approach completely dead?

Chang’s theorem doesn’t give a strong enough bound to improve the Roth/Meshulam bound. And Chang’s theorem itself cannot be hugely improved, as the above example shows. (With a bit of messing about, one can modify the example to provide examples for different values of .) So there is no hope of using this kind of approach to improve the bounds for the cap-set problem.

Or is that conclusion too hasty? Here are two considerations that should give us pause.

1. The example above that showed that Chang’s theorem is best possible does not have the kind of spectrum that a set with no arithmetic progressions would have. In particular, there does not exist such that, up to log factors,

Fourier coefficients have size at least

(If we take

then we get only

such coefficients.)

2. There are other ways one might imagine improving Chang’s theorem. For instance, suppose we are given Fourier coefficients of size

We know that they must all live in a

-dimensional subspace, but it is far from clear that they can be an arbitrary set of points in a

-dimensional subspace. (All the time I’m ignoring log factors.)

Let me discuss each of these two considerations in turn.

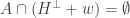

Is there an example that completely kills the density-increment approach?

Just to be clear, the density-increment approach to the theorem is to show that if a set of density

does not contain an arithmetic progression of length 3, then there is some subspace

of small codimension such that the density of

in

is at least

The Roth/Meshulam argument allows us to take

with a codimension of 1. If we could take

to be substantially more than

on a subspace of codimension

then we would be in excellent shape. Conversely, if we could find an example where this is not possible, then we would place significant limitations on what the proof of an improved bound could look like.

Again we face the problem of deciding what “an example” means, since we are not trying to construct dense sets with no arithmetic progressions. I find that I keep coming back to the following precise question.

Question 1. Let and

be three subsets of

each of density

Suppose that there are no solutions to the equation

with

and

For what values of

and

can we say that there must be an affine subspace

of codimension

such that the density of

in

is at least

?

The Roth/Meshulam argument implies that we can take and

The following example shows that we can’t do much better than

when

(I don’t claim that it is hard to improve on this example, but I can’t do so after five minutes of thinking about it). Pick

such that

(Again, one can obtain a larger

by taking a product.) Let

be a random subset of

of density

Then

has size bounded above by approximately

which means that it must miss around half of

so we can find

of the same density such that

Since is random, its non-trivial Fourier coefficients will be around

(Again, I am ignoring a log factor that is due to the fact that a few Fourier coefficients will be unexpectedly large. Again, quadratic examples can take care of this.)

Now note that in the above example we took to be proportional to

That means that if we are prepared to lose only

dimensions, we can get the density up to 1. So the obvious next case to think about is how big a density increase we can hope for if we are prepared to drop that many dimensions.

We certainly can’t hope to jump all the way to 1. A simple example that shows this is to let be a random subset of

of density

in

and to let

be a subset of

Then the relative density of

in an affine subspace

will be

approximately

or approximately

according to whether

is disjoint from

neither disjoint from nor contained in it, or contained in it — unless, that is, we are prepared to drop down to a very low dimension indeed, where the codimension depends on

Thus, the best density increase it is reasonable to aim for is one that is proportional to the existing density.

Putting these thoughts together, it is tempting to ask the following question, which is a more specific version of Question 1.

Question 2. Let and

be above. Can we take

proportional to

and

proportional to

?

If the answer to this question is yes, then it implies a bound for the problem of a huge improvement on the Roth/Meshulam bound of

Writing

for

we can rewrite this bound as

which is of the same form as the Behrend bound in

This is suggestive, but so weakly suggestive that I’m not sure it should be taken seriously.

I should stress that a counterexample to this rather optimistic conjecture would be very interesting. But it is far from clear to me where a counterexample is going to come from, since the examples that show that Chang’s theorem is best possible do not appear to have enough large Fourier coefficients to have no arithmetic progressions.

[Added later: Ben Green makes an observation about Questions 1 and 2 in a comment below, which demands to be mentioned here since it places them in a context about which plenty is known, including exciting recent progress due to Tom Sanders. Suppose that Question 2 has a positive answer, say. Let be a set of density

Then either

or there exists

such that

does not contain 0. In the latter case, we can set

and

equal to

and

equal to

and Question 2 tells us that there must be a codimension-

subspace (where

) inside which

has density

We cannot iterate this argument more than

times before reaching a density of 1, so

must contain a subspace of codimension at most

which is stronger than the best known result in this direction, due to Sanders.

However, Sanders’s result is in the same territory: he shows that contains a subspace of codimension at most a fixed power of

in this paper. Usually what you can do for four sets you can do for three — I haven’t checked that that is true here, but maybe somebody else has (Tom, if you are reading this, perhaps you could confirm it). Thus, even if it looks a bit optimistic to prove a positive answer to Question 2, one can still hope for a positive answer with the bound slightly weakened, to say

or something like that. Furthermore, the fact that Sanders has proved what he has proved suggests that there could be techniques out there, such as the Croot-Sisask lemma, that would be extremely helpful. (However, it is clear that Sanders, Croot and Sisask have thought pretty hard about what they can get out of these techniques, so a cheap application of them seems unlikely to be possible.)]

What can the large spectrum look like?

The following argument is excerpted from the proof of Chang’s theorem. Let be a set of density

and let

be the characteristic function of

Let

be a subset of

such that

for every

Let

be the function

and recall that

by the inversion formula.

Then

Also, for any and

such that

Hölder’s inequality tells us that

Now which is close to

when

is large, and within a constant of

when

reaches

.

In order to think about let us make the simplifying (and, it turns out, not remotely problematic) assumption that

is an even integer

Then a standard calculation (or easy use of the convolution identity) shows that

We therefore know that

is at least

To get a feel for what this is telling us, let us bound the left-hand side by replacing each Fourier coefficient by That tells us that

times the number of

-tuples

such that

is at least

Therefore, the number of these

-tuples is at least

Now a trivial lower bound for the number of the -tuples is

If the number is roughly equal to this lower bound, then we obtain something like the inequality

which implies that

For example, if and

then this tells us that we cannot have a subset

of the large spectrum of size

without having on the order of

non-trivial quadruples

Even this example (which is not the that Chang considers — she takes

to be around

) raises an interesting question. Let us write

for

Then if we cannot improve on the Roth/Meshulam bound, we must have (up to log factors) a set

of size

such that amongst any

of its elements there are at least as many non-trivial additive quadruples

as there are trivial ones: that is, at least

such quadruples.

Sets with very weak additive structure.

What does this imply about the set ? The short answer is that I don’t know, but let me give a longer answer.

First of all, the hypothesis (that every subset of size spans some non-trivial additive quadruples) is very much in the same ball park as the hypotheses for Freiman’s theorem and the Balog-Szemerédi theorem, in particular the latter. However, the number of additive quadruples assumed to exist is so small that we cannot even begin to touch this question using the known proofs of those theorems.

Should we therefore say that this problem is way beyond the reach of current techniques? It’s possible that we should, but there are a couple of reasons that I think one shouldn’t jump to this conclusion too hastily.

To explain the first reason, let me consider a weakening of the hypothesis of the problem: instead of assuming that every set of size spans at least

non-trivial additive quadruples, let’s just see how many additive quadruples that tells us there must be and assume only that we have that number.

This we can do with a standard double-counting argument. If we choose a random set of size our hypothesis tells us it will contain at least

non-trivial additive quadruples. But the probability that any given non-trivial additive quadruple

belongs to the set is

so if the total number of non-trivial additive quadruples is

then

must be at least

(counting the expected number of additive quadruples in a random set in two different ways). That is,

must be at least

This is to be contrasted with the trivial lower and upper bounds of

and

Here are two natural ways of constructing a set with that many additive quadruples. The first is simply to choose a set randomly from a subspace of cardinality

The typical number of additive quadruples if

is

so we want to take

and thus to take

The dimension of this subspace is therefore logarithmic in

which means that the entire large spectrum is contained in a log-dimensional subspace, which gives us a huge density increase for only a small cost in dimensions.

The second is at the opposite extreme: we take a union of subspaces of cardinality

for some

The number of non-trivial additive quadruples is approximately

so for this to equal

we need

to be

and

to be

Note that here again we are cramming a large portion of the large spectrum into a log-dimensional subspace.

So far this is quite encouraging, but we should remind ourselves (i) that there could be some much more interesting examples than these ones (as I write it occurs to me that finite-fields niveau sets are probably worth thinking about, for instance) and (ii) that even if the most optimistic conjectures are true, they seem to be very hard to prove with this level of weakness of hypothesis.

A quick remark about the second example. If we choose points at random from each of the

subspaces of size

then those points will span around

additive quadruples, so in total we will get around

additive quadruples. This is how to minimize the number of additive quadruples in a set of size

so in the second case (as well as the first) we also have the stronger property that every subset of size

contains at least

non-trivial additive quadruples.

Going back to the point that we are assuming a very weak condition, the main reason that that doesn’t quite demonstrate that this approach is hopelessly difficult is that we can get by with a very weak conclusion as well. Given the very weak hypotheses, one can either say, “Well, it looks as though A ought to be true, but I have no idea how to prove it,” or one can say, “Let’s see if we can prove anything non-trivial about sets with this property.” As far as I know, not too much thought has been given to the second question. (If I’m wrong about that then I’d be very interested to know.)

I’ve basically given the argument already, but let me just spell out again what conclusion would be sufficient for some kind of improvement to the current bound. For the purposes of this discussion I’ll be delighted with a bound that gives a density of (since that would be below the magic

barrier and would thus raise hopes for beating that barrier in Roth’s theorem too).

As ever, I’ll take to equal

so that we have around

Fourier coefficients of size around

If

of these are contained in a

-dimensional subspace

then the sum of squares of all the Fourier coefficients in

is at least

which gives us a coset of

in which the density is increased by

This is an improvement on the Roth/Meshulam argument provided only that

is significantly bigger than

or in other words

is significantly bigger than

So here is a question, a positive answer to which would give a weakish, but definitely very interesting, improvement to the Roth/Meshulam bound. I’ve chosen some arbitrary numbers to stick in rather than asking the question in a more general but less transparent form. But if you would prefer the latter, then it’s easy to modify the formulation below.

Question 3. Let be a subset of

of size

that contains at least

quadruples

Does it follow that there is a subspace of

of dimension at most

that contains at least

elements of

?

I talked about very weak conclusions above. The justification for that description is that we are asking for the number of points of in the subspace to be around the cube of the dimension, whereas the cardinality of the subspace is exponential in the dimension. So we are asking for only a tiny fraction of the subspace to be filled up. This is much much weaker than anything that comes out of Freiman’s theorem.

To give an idea of the sort of argument that it makes available to us that is not available when one wishes to prove Freiman’s theorem, let us suppose we have a set of size

such that no subspace of dimension

contains more than

points, and let us choose from

a random subset

picking each element with probability

Given any subspace of dimension the expected number of points we pick in that subspace is at most

and the probability that we pick at least

points is at most around

The number of subspace of dimension

that contain at least

points of

is at most

which is at most

If we take

to be

then the expected number of these subspaces that contain at least

points is less than 1.

On the other hand, if the number of additive quadruples in was at least

then the expected number in our random subset is at least

while the size of that subset is around

The precise numbers here are not too important. The point is that this random subset is a set of size

that contains

additive quadruples for some

such that no subspace of dimension

contains more than

points of

And we have a certain amount of flexibility in the values of

and

Thus, to improve on the bounds for the cap-set problem it is enough to show that having

additive quadruples implies the existence of a subspace of dimension

for some small

(or even smaller dimension if one is satisfied with a yet more modest improvement to the Roth/Meshulam bound) that contains a superlinear number (in the dimension of the subspace) of points of

This is promising, partly because it potentially allows us to use the stronger hypothesis that we were actually given about Recall that the

bound for the number of additive quadruples was actually derived from the fact that every subset of

of size

contains at least

non-trivial additive quadruples. So one thing we might try to do is assume that we have a set

of size

such that no subspace of dimension

contains more than

points of

and try to use that to build inside

a largish subset (of size

say) that has very few additive quadruples.

Let me end this section with a reminder that we have by no means explored all the possibilities that arise out of Chang’s argument. I have concentrated on the case (and thus

) because it is easy to describe and because it relates rather closely to existing results in additive combinatorics. But if it is possible to use these ideas to obtain a big improvement to the Roth/Meshulam bound, then I’m pretty sure that to do so one needs to take

to be something closer to

as Chang does in her theorem. The arguments I have been sketching have their counterparts in this range too. In short, there seems to be a lot of territory round here, and I suspect that not all of it has been thoroughly explored.

Is there a simple and direct way of answering Question 2?

Let me begin with a reminder of what Question 2 was. Let and

be three subsets of

each of density

Suppose that there are no solutions to the equation

with

and

Then Question 2 asks whether there is an affine subspace

of codimension

such that the density of

inside

is at least

The Roth/Meshulam argument gives us a density of in a codimension-1 subspace, and it does so by expanding and applying simple identities and inequalities such as Parseval and Cauchy-Schwarz to the Fourier coefficients. Now Fourier coefficients are very closely related to averaging projections onto cosets of 1-codimensional subspaces (a remark I’ll make more precise in a moment). Can we somehow generalize the Roth/Meshulam argument and look at an expansion in terms of averaging projections to cosets of

-codimensional subspaces, with

? Is there a very simple argument here that everybody has overlooked? Probably not, but if there isn’t then it at least seems worth understanding where the difficulties are, especially as quite a lot of the Roth/Meshulam argument does generalize rather nicely.

Expanding in terms of projections.

[Added later: While looking for something else, I stumbled on a paper of Lev, which basically contains all the observations in this section.]

For the purposes of this section it will be convenient to work not with the characteristic functions of and

but with their balanced functions, which I shall call

and

The balanced function of a set

of density

is the characteristic function minus

That is, if

then

and otherwise

The main properties we shall need of the balanced function are that it averages zero and that if it averages

in some subset of

then

has density

inside that subset.

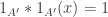

Here is another simple (and very standard) lemma about balanced functions. Suppose we pick a random triple of elements of

such that

Then the probability that it lies in

is

This sum splits into a sum of eight sums, one for each way of choosing either the first or the second term from each bracket. But since and

all average zero, all but two of these terms disappear. For example,

is zero since it equals

which in turn equals

Thus, the probability in question is

In particular, if it is zero, then

Let be a linear subspace of

of codimension 1. Then

is of the form

for some

(which is unique up to a scalar multiple), where

stands for the sum

in

Let us write

for the function

defined by setting

to be the average of

over all

Thus,

is the averaging projection that maps a function to the nearest function that is constant on cosets of

Let us now relate this to the Fourier expansion of

I shall do it by a direct calculation, but it can be understood conceptually: if we restrict the Fourier transform to a subspace, then we convolve the original function by the annihilator of that subspace.

By the inversion formula, we have that

where Now let us pick a non-zero

and consider the sum

Note that we are adding up over all Fourier coefficients at multiples of Expanding the Fourier coefficients, we obtain the sum

The term in brackets is 3 when and 0 otherwise. If

is the subspace

then this says that the term in brackets is 3 if

and

lie in the same coset of

and 0 otherwise. Since the probability that they lie in the same coset is 1/3, this tells us that the sum is nothing other than

An additional observation, and our reason for using balanced functions, is that if averages zero, then

Therefore, in this case we have the identity

and also (by the inversion formula and the fact that the pairs partition the non-zero elements of

) the identity

where the sum is over all subspaces of codimension 1.

Since the functions form an orthonormal basis, we can also translate Parseval’s identity into the form

and more generally

What about counting arithmetic progressions of length 3? Well, expands as

Interchanging summation we obtain

Now the three functions

and

all average zero, and they are constant on cosets of

and

respectively. If

and

are not all equal, then the inner expectation must be zero. To see this, let

and

be vectors “perpendicular” to

and

respectively. Then

if and only if there exists

that cannot be written as

with

That is the case if and only if there is a multiple

of each of

and

such that

(Why? Well if there is such a multiple then it is obvious. Conversely, if

is not in

then there must be a linear functional

that vanishes on

but not at

If that linear functional is

then

must be a multiple of each of

and

) Such

exist if and only if

and

are all multiples of each other, which happens if and only if

and

are all equal.

Therefore, the AP count can be rewritten as

In words, the AP count is obtained by summing the AP counts over all codimension-1 averaging projections.

Now the size of that last expression is bounded above by

By the projections version of Parseval’s identity, the sum of those inner products is so the assumption that there are no APs in

implies that

Since and

are at most

we find that

which implies that there is a coset of some

in which

averages at least

(The factor 1/2 comes from the fact that

might have its

norm by virtue of

averaging

on a coset. But since

averages zero, we then get at least

on one of the other two cosets.)

What I have just done is recast the Roth/Meshulam argument in terms of averaging projections rather than Fourier coefficients — but it is basically the same argument. What was the point of doing that? My motivation was that the projections version gives me something I can generalize to subspaces of higher codimension.

Expanding in terms of higher-codimension averaging projections.

A lot of what I said in the last section carries over easily to the more general situation where we sum over higher-codimension averaging projections. Let us fix a and interpret all sums over subspaces as being over the set of all subspaces of codimension

Our first identity in the case

was

What happens for general ? Well,

Let us write for the number of codimension-

subspaces of

Then the number of codimension-

subspaces that contain

is

if

and

otherwise (since the probability that a random codimension-

subspace contains

is equal to the number of non-zero points in such a subspace divided by the total number of non-zero points in

). Therefore, the sum above works out as

The contribution from the second term is zero, since averages zero, so we get

Thus, is proportional to

with a constant of proportionality that is not too hard to estimate.

Next, let us prove a version of Parseval’s identity.

Now the number of subspaces containing depends on the dimension of the space spanned by

and

However, if we sum

over all pairs

then we get zero (since

averages zero). If we sum over all pairs of the form

for some

then we get zero, since every pair

can be written in

ways as

The same applies to pairs of the form

and pairs of the form

Finally, if we sum over pairs of the form

we get a multiple of

with a larger multiple (by a factor of roughly

) if

Putting this together, we find that is proportional to

again with a constant of proportionality that, with a bit of effort, one can estimate fairly accurately. Once again, this implies (by polarization or by generalizing the proof) that

is proportional to

Finally, let us prove that the AP count of is proportional to the sum of the AP counts of the projections. We have

The value of depends only on the dimension of the subspace spanned by

The sum of

over all

is zero. The sum over all

that satisfy a non-trivial linear relation

is zero unless

(because unless that is the case we can express any triple in the form

with

and

and the result is proportional to

). The sum over all

such that

is proportional to

Putting all this together tells us that

is proportional to as claimed. What is potentially significant about this is that if we can use it to show that there is some

of low codimension such that the AP count of

is reasonably large, then there must be some coset of

on which

has reasonably large average.

At this point, honesty compels me to mention that the above facts can be proved much more simply on the Fourier side — so much so that it casts serious doubt on whether one could get anything out of this “codimension- expansion” that one couldn’t get out of the normal Fourier expansion. All we have to do is point out that the Fourier expansion of

is the restriction of

to

and that if

sums to zero then

From this it follows easily that the Fourier transform of

is proportional to

that

is proportional to

and that

is proportional to

From those facts, the results above follow easily.

Thus, all we are doing by splitting up into the functions is splitting up the Fourier transform of

as a suitable average of its restrictions to the subspaces

(and using the fact that

— all non-zero points will be in the same number of subspaces

). How can that possibly tell us anything that we can’t learn from examining the Fourier transform directly?

The only answer I can think of to this question is that it might conceivably be possible to prove something by looking at some function of the projections that does not translate easily over to the Fourier side. I have various thoughts about this, but nothing that is worth posting just yet.

So what was the point of this section? It’s here more to ask a question than propose an answer to anything. The question is this. If it really is the case that for every AP-free set (or AP-free triple of sets ) there must be a fairly low-codimensional subspace

such that variations in density show up even after one applies the averaging projection

then it seems highly plausible that some kind of expression in terms of these expansions should be useful for proving it. For instance, we might be interested in the quantity

where

is the balanced function of

And perhaps we might try to analyse that by looking instead at

for some suitably chosen large integer

(to get a handle on the maximum but also to give us something we can expand and think about). The question is, can anything like this work? I don’t rule out a convincing negative answer. One possibility would be to show that it cannot give you anything that straightforward Fourier analysis doesn’t give you. A more extreme possibility is that the rather optimistic conjecture about getting a large density increment on a low-codimensional subspace is false. The latter would be very interesting to me as it would rule out a lot of approaches to the problem.

Conclusion.

I don’t really feel that I’ve come to the end of what I want to say, but I also feel as though I am never going to reach that happy state, so I am going to cut myself off artificially at this point. Let me end by briefly discussing a question I mentioned at the beginning of this post: is this the beginning of a Polymath project?

It isn’t meant to be, partly because I haven’t done any kind of consultation to see whether a Polymath project on this problem would be welcome. For now, I see it as very much in the same spirit as Gil Kalai’s “open discussion”. What I hope is that some of my remarks will provoke others to share some of their thoughts — especially if they have tried things I suggest above and can elaborate on why they are difficult, or known not to work. If at some point in the future it becomes clear that there is an appetite for collectively pursuing one particular approach to the problem, then at that point we could perhaps think about a Polymath project.

Should there be ground rules associated with an open discussion of a mathematical problem? Perhaps there should, but I’m not sure what they should be. I suppose if you use a genuine idea that somebody has put forward in the discussion then it is only polite to credit them: in any case, the discussion will be in the public domain so if you have an idea and share it then it will be date-stamped. If anyone has any further suggestions about where trouble might arise and how to avoid it then I’ll be interested to hear them.

January 11, 2011 at 3:51 pm |

I guess these are called “cap sets” because they cap the number of cards you can have in the Set game without having a set.

January 11, 2011 at 5:00 pm |

I was once told that cap-sets, which are investigated in various geometries, are called like this, since the shape of a cap (in the sense of headgear) resembles a form not containing three colinear points. Some other terms used in this context, e.g., oval or ovoid, seem to have a similar origin.

January 11, 2011 at 6:15 pm |

Tim,

Thanks for this interesting post. Here is a thought that occurred to me whilst reading it, and which I haven’t looked at in any detail yet. Your question 2 seems to be pretty close to some well-known unsolved problems connected with (and in fact stronger than) the polynomial Freiman-Ruzsa conjecture (PFR). In particular it is conjectured that A + B contains 99 percent of a subspace of codimension C log (1/\alpha), so if A + B doesn’t meet -C then C will definitely have some biases on subspaces of that kind of dimension. This conjecture implies the “polynomial Bogolyubov conjecture”, which is known to imply PFR but is not known to follow from it. I’ll have to think about how your question fits into this circle of ideas.

Actually, as I write this, it occurs to me that if your question holds then either A + A + A is everything or else A has doubled density on a subspace of codimension log (1/\alpha). So by iteration you get that A + A + A contains a subspace of codimension log^2 (1/\alpha), if I’m not mistaken. This is already better than known bounds for Bogolyubov-type theorems (there is a very recent paper of Sanders in which he gets log^4 (1/\alpha) I believe).

It would be interesting to know whether you can reverse the implication (P Bogolyubov => weak form of Q2 => improvements on cap sets) . I think Sanders and Schoen have done some work on related issues — if instead of solving x + y = 2z you want to solve x + y + z = 3w I think they have something new to say.Tom Sanders will be able to supply the details.

January 11, 2011 at 6:35 pm

I don’t quite understand your point about A+A+A here. If A has doubled density, I don’t see how you then iterate, because you no longer know about the densities of B and C. Also, although the result might be stronger than known Bogolyubov theorems (though that’s not a disaster as one could simply allow the codimension to be a bit larger), the assumption is a bit different.

Ah, in writing that I see a very elementary pint that I’d missed (despite knowing it in many other contexts), namely that what I’m assuming is strictly weaker than assuming that the density of A+A is at most I’ll have a think about whether I want to modify what I’ve written.

I’ll have a think about whether I want to modify what I’ve written.

January 11, 2011 at 7:18 pm |

Tim,

On the first iteration I plan to take A = B and C = A – x, where x is some element not in A + A+ A. This gives me A’, a set with density 2\alpha on F_3^{n’} with n’ >= n – O(log (1/\alpha). Now if A’ + A’ + A’ is everything (in F_3^{n’}) I’m done; otherwise repeat. Doesn’t this work?

Ben

January 11, 2011 at 7:25 pm

In between replying to your previous comment and replying to this I had a bath, during which I understood properly what you were saying — and indeed it works.

January 11, 2011 at 10:08 pm |

Dear Tim,

I had in mind a somewhat different approach to improving upon the Roth-Meshulam bound that I think I can describe fairly painlessly: suppose that is a subset of

is a subset of  of density

of density  , where we take

, where we take  as close to

as close to  as we please and

as we please and  (the goal is to show that

(the goal is to show that  ). Then, of course, if

). Then, of course, if  is small enough the Roth-Meshulam approach will just fail to work. However, if you do about

is small enough the Roth-Meshulam approach will just fail to work. However, if you do about  Roth iterations (passing to hyperplanes each time), what you will wind up with is a subspace

Roth iterations (passing to hyperplanes each time), what you will wind up with is a subspace  of dimension about

of dimension about  and a set

and a set  such that the following hold:

such that the following hold:

1. First, if contains a 3AP in

contains a 3AP in  , then

, then  contains a 3AP in

contains a 3AP in  .

.

2. Let be the set of all

be the set of all  having at most

having at most  representations as

representations as  where

where  . Then, second, we have that

. Then, second, we have that  is a positive density subset (the density will be a function of

is a positive density subset (the density will be a function of  ) of

) of  . In other words,

. In other words,  is a dense subset of a level-set of a sumset.

is a dense subset of a level-set of a sumset.

Now, if we knew that were roughly translation-invariant by a couple different directions

were roughly translation-invariant by a couple different directions  (where, say,

(where, say,  ), then we would expect that there exists

), then we would expect that there exists  such that

such that  , where

, where  . In other words, there is a shift of a low-dimensional (but not too low) subspace

. In other words, there is a shift of a low-dimensional (but not too low) subspace  that intersects

that intersects  in many points. Upon applying Roth-Meshulam to this intersection we’d be done, since then

in many points. Upon applying Roth-Meshulam to this intersection we’d be done, since then  would contain a 3AP, implying that

would contain a 3AP, implying that  contains a 3AP, implying that

contains a 3AP, implying that  contains a 3AP.

contains a 3AP.

But could we show that is translation-invarant by many directions? Well, it turns out that my work with Olof is just barely too weak to do this — if we could improve our method only a tiny bit, we’d be done (basically, we would try to show that the function

is translation-invarant by many directions? Well, it turns out that my work with Olof is just barely too weak to do this — if we could improve our method only a tiny bit, we’d be done (basically, we would try to show that the function  is roughly translation-invariant by a lot of directions, which would imply that various level-sets of this function are roughly translation-invariant; our method works so long as the density of

is roughly translation-invariant by a lot of directions, which would imply that various level-sets of this function are roughly translation-invariant; our method works so long as the density of  is just larger than about

is just larger than about  ).

).

What I plan to do is to generalize mine and Olof’s results so that we can work with densities somewhat below , and where I replace “translation-invarance” with some other property. I can prove *some* non-trivial things about the function

, and where I replace “translation-invarance” with some other property. I can prove *some* non-trivial things about the function  by generalizing our arguments in a trivial way (the sort of things that are pretty much hopeless to show using Fourier methods as we currently understand them); and I suspect that much more will follow once I have a chance to seriously think about it.

by generalizing our arguments in a trivial way (the sort of things that are pretty much hopeless to show using Fourier methods as we currently understand them); and I suspect that much more will follow once I have a chance to seriously think about it.

By the way… Seva Lev once emailed me some constructions of sets giving very little density gain under multiple Roth iterations. I forget what bounds he got exactly, however. Perhaps you should email him.

January 16, 2011 at 11:25 am

Ernie, I have trouble understanding your interesting-looking argument. Here are a few questions.

1. When you say that after n/2 Roth iterations you get with certain properties, is that supposed to be obvious, or is there an argument you are not giving that tells us that

with certain properties, is that supposed to be obvious, or is there an argument you are not giving that tells us that  has properties that we cannot assume for the original set

has properties that we cannot assume for the original set  ? Either way, how are these n/2 Roth iterations helping us?

? Either way, how are these n/2 Roth iterations helping us?

Actually, that’s my only question for now. I get a bit lost in the paragraph after your property 2, so if you felt like expanding on that, it would also be very helpful.

January 16, 2011 at 10:42 pm

[1. When you say that after…]

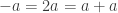

Actually, that part is fairly easy to do. Starting with a subset A of having density about

having density about  , two things can happen: either all the non-trivial Fourier coefficients are smaller than about

, two things can happen: either all the non-trivial Fourier coefficients are smaller than about  , or there is at least one that is larger than this in magnitude. If we are in the former case, then just writing the number of 3APs in terms of Fourier coefficients we quickly see that

, or there is at least one that is larger than this in magnitude. If we are in the former case, then just writing the number of 3APs in terms of Fourier coefficients we quickly see that  contains 3APs. And if we are in the latter case, just doing one Roth iteration will boost the relative density (on a hyperplane) by a factor

contains 3APs. And if we are in the latter case, just doing one Roth iteration will boost the relative density (on a hyperplane) by a factor  .

.

Now let’s suppose that we do this for iterations, and that for each iteration we can *always* find a Fourier coefficient where we can do a little better: instead having one of size at least

iterations, and that for each iteration we can *always* find a Fourier coefficient where we can do a little better: instead having one of size at least  , we always find one of size at least

, we always find one of size at least  , resulting in a magnification in the density after each iteration by a factor

, resulting in a magnification in the density after each iteration by a factor  . When we do this

. When we do this  times, we end up with a set whose relative density inside

times, we end up with a set whose relative density inside  (assume

(assume  is even) has size

is even) has size

That density is just large enough that the standard Roth-Meshulam bound guarantees that our set has 3APs.

So either we prove that our set has 3APs by the th iteration, or else at *some* iteration all the non-trivial Fourier coefficients are

th iteration, or else at *some* iteration all the non-trivial Fourier coefficients are  times as large as at the principal character.

times as large as at the principal character.

Now, if we find ourselves in this latter case, then it means we have passed to a set that is fairly quasirandom inside some space

that is fairly quasirandom inside some space  , where

, where  . It is *so* quasirandom, in fact, that standard arguments show that

. It is *so* quasirandom, in fact, that standard arguments show that  for all but at most

for all but at most  places

places  (here,

(here,  is normalized to just be the count of the number of solutions

is normalized to just be the count of the number of solutions  ,

,  ).

).

If contains no 3APs, then for any

contains no 3APs, then for any  we must have

we must have  (there is always the trivial solution

(there is always the trivial solution  ). What this means is that if

). What this means is that if  has no 3APs, then

has no 3APs, then  must be a subset of those

must be a subset of those  places where

places where  . And in fact, this means that

. And in fact, this means that  is then a positive-density subset of a particular level-set of

is then a positive-density subset of a particular level-set of  !

!

If we just knew that this level set was roughly a union of cosets of some subspace of not-too-low-dimension, then one of those cosets would intersect in a positive density of elements… and then we’d be done. Alas, my work with Olof is just barely too weak to show this — if the set

in a positive density of elements… and then we’d be done. Alas, my work with Olof is just barely too weak to show this — if the set  were just of slightly higher density a direct application of our methods would indeed show exactly what we need (covering by cosets).

were just of slightly higher density a direct application of our methods would indeed show exactly what we need (covering by cosets).

Tom’s recent work on Bogolyubov seems like the obvious idea to try at this point, since it even works with very low-density sets. However, his result only shows that there is a large subspace meeting the set in a high proportion of the points of that subspace; it does *not* show that the level-sets of

in a high proportion of the points of that subspace; it does *not* show that the level-sets of  can be *covered* by cosets of that subspace. I have actually thought some on Tom’s proof, and it seems that it is too “local” to get this type of conclusion without some modifications.

can be *covered* by cosets of that subspace. I have actually thought some on Tom’s proof, and it seems that it is too “local” to get this type of conclusion without some modifications.

Fortunately, I don’t think we have quite reached the limit of what my work with Olof can achieve…

January 16, 2011 at 10:43 pm

Oops… everywhere I wrote $latec A^(0)$ I should have written .

.

January 17, 2011 at 6:02 am

Also, where I wrote , I meant

, I meant  . (Too bad wordpress doesn’t allow one to edit ones comments.)

. (Too bad wordpress doesn’t allow one to edit ones comments.)

January 17, 2011 at 9:04 am

That non-feature of WordPress is indeed very irritating.

I’m in the middle of a new post, and, interestingly, some of what you write above is very similar to things that I have written in the post. I won’t say more for now, but will try to finish the post as soon as I can.

January 13, 2011 at 10:18 pm |

The problem is indeed fascinating. One basic example is all 0,1 vectors. One idea I thought about variations of this example which may be useful was this: suppose that n is a power of 4 and let the n coordinates organized at the leaves of a 4-regular tree. When the variables are labeled 0, 1, 2 label inductively each internal vertex 2 if at least 2 of the sons is labeled 2. Otherwised label it 0 or 1. Consider all vectors of 0,1,2, so that the root is labelled 0 or 1. for three such vectors x y and z there is a son of the root they all are labeled 0 or 1 this goes all the wat to a single variable they all ar elabeled 0 and 1. so there is now x+y+z=0. The point is to find example base don somehow importing some Boolean function we have.

January 13, 2011 at 10:33 pm

(this was a bit silly since in a coordinate with no 2 the three entries can still be the same. in any case, I had the vague hope that using some sircuits or formulas expressing relations between the coordinates may lead to interesting examples. )

January 14, 2011 at 6:51 am |

Sorry, part of my post seems not to have appeared. There’s an unfortunate skip between d/N^2 and S. I think it is because blogger

gets upset when it sees two less than signs together. I have replaced my double

less thans with less thans.

Let me try again.

Dear Tim,

Michael Bateman and I have worked, unsuccessfully, quite a bit on the cap set problem along the lines which you suggest. The spectrum of a capset with no increments better than Meshulam’s in fact has much better structure than your blog post suggests. It has largish subsets which are close to additively closed but not quite close enough by our bookkeeping to get an improvement.

Let us suppose that is a capset of size almost

is a capset of size almost  in

in  Let

Let  be the set of frequencies where

be the set of frequencies where  shows bias of at least almost

shows bias of at least almost  It can never be much more than

It can never be much more than  or we automatically have a better increment. You show that

or we automatically have a better increment. You show that  is about

is about  and that

and that  has at least

has at least  additive quadruples. But, in fact, the situation is much sharper than this because

additive quadruples. But, in fact, the situation is much sharper than this because  has no more than

has no more than  additive quadruples. Moreover, things don’t get better when you look at higher tuples.

additive quadruples. Moreover, things don’t get better when you look at higher tuples.  has at most

has at most  sextuples,

sextuples,  octuples and so forth.

octuples and so forth.

Here’s a sketch of a proof. We have the Fourier argument which appears in your post controlling how much spectrum can be in a subspace. In particular, a subspace of dimension may contain no more than

may contain no more than  elements of the spectrum. (At least this is true for

elements of the spectrum. (At least this is true for  where none of the Meshulam increments are substantially better than the first.)

where none of the Meshulam increments are substantially better than the first.)

This tells us a lot about how linearly independent must be small random selections from If I have already selected

If I have already selected  elements from

elements from  at random without replacement and I am about to select a

at random without replacement and I am about to select a  st, then the span of the elements I have already selected is at most

st, then the span of the elements I have already selected is at most  so the probability that the

so the probability that the  st element lives in the span is at most

st element lives in the span is at most  Thus if I take a random selection without replacement of almost

Thus if I take a random selection without replacement of almost  elements, then they have a good chance (better than

elements, then they have a good chance (better than  ) of being linearly independent and indeed the probability that they have nullity

) of being linearly independent and indeed the probability that they have nullity  is exponentially decreasing in

is exponentially decreasing in  We let

We let  be this random selection and we ask ourselves how many

be this random selection and we ask ourselves how many  -tuples come entirely from elements of

-tuples come entirely from elements of  We choose a maximal linearly independent set of all vanishing linear combinations of elements of

We choose a maximal linearly independent set of all vanishing linear combinations of elements of  which consist of at most

which consist of at most  elements of

elements of  This set consists of at most

This set consists of at most  elements because

elements because  has nullity

has nullity  so it involves at most

so it involves at most  elements of

elements of  Therefore there are at most

Therefore there are at most  many

many  -tuplets in

-tuplets in  This grows only polynomially in

This grows only polynomially in  with

with  fixed. Therefore the expected number of

fixed. Therefore the expected number of  -tuplets is bounded above by a constant depending only on

-tuplets is bounded above by a constant depending only on

However suppose that has many more than

has many more than  octuplets. For some

octuplets. For some  it will have substantially more than

it will have substantially more than

-tuplets and therefore, the expected number of

-tuplets and therefore, the expected number of  -tuplets in

-tuplets in  will be more than a constant. This is a contradiction.

will be more than a constant. This is a contradiction.

So we really can expect octuplets in

octuplets in  and no more. What good does that do? A hint at the answer lies in a paper of mine with Paul Koester which has been getting a fair amount of attention lately. In that paper, what Paul and I did was to try to quantify the structure of nearly additively closed sets by how much they get better when you add them to themselves. The result was in any case to get slight better energy than one might expect for a subset of the sumset. The extremes of the range of examples we had in mind were a) random set + subspace and b) random subset of subspace. In the case a) the sumsets never get better – the subspace stays the same and the random set expands. Let us call that, for the sake of this message, the additively non-smoothing case. The example b) is just the opposite. Add it to itself once and you get whole subspace. In our paper, we put every additive set somewhere in a continuum between these two examples. However, if we know in advance that there no more octuplets than Holder requires, then we have no additive smoothing and this means we are stuck close to example a). Let me show a little more rigorously how this works in our present situation.

and no more. What good does that do? A hint at the answer lies in a paper of mine with Paul Koester which has been getting a fair amount of attention lately. In that paper, what Paul and I did was to try to quantify the structure of nearly additively closed sets by how much they get better when you add them to themselves. The result was in any case to get slight better energy than one might expect for a subset of the sumset. The extremes of the range of examples we had in mind were a) random set + subspace and b) random subset of subspace. In the case a) the sumsets never get better – the subspace stays the same and the random set expands. Let us call that, for the sake of this message, the additively non-smoothing case. The example b) is just the opposite. Add it to itself once and you get whole subspace. In our paper, we put every additive set somewhere in a continuum between these two examples. However, if we know in advance that there no more octuplets than Holder requires, then we have no additive smoothing and this means we are stuck close to example a). Let me show a little more rigorously how this works in our present situation.

We have a set of size

of size  with at least approximately

with at least approximately  quadruples and at most

quadruples and at most  octuples. I will aim at something very modest which is not nearly strong enough to imply a cap set improvement but which seems a great deal stronger than the structure you have indicated in your post. Namely there is a subset

octuples. I will aim at something very modest which is not nearly strong enough to imply a cap set improvement but which seems a great deal stronger than the structure you have indicated in your post. Namely there is a subset  of

of  with the size of

with the size of  at least

at least  so that there is

so that there is  with

with  and with

and with  [We can do a little better but still not enough to do any good.]

[We can do a little better but still not enough to do any good.]

I have written my claim so that I never have to be self-conscious about dyadic pigeonholing. [And by the bookkeeping I can do, much of this falls apart without it. I omit all logs that appear. This is in fact a problem.]

Thus, I can start out with a set so that

so that  so that the sums in

so that the sums in  are all popular: that is

are all popular: that is  with

with  and I assume each sum is represented

and I assume each sum is represented  ways and each element

ways and each element  appears as a summand in

appears as a summand in  sums.

sums.

As in my paper with Koester for we define the set

we define the set ![D[x]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5Bx%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to consist of all summands of

to consist of all summands of  or if you

or if you![D[x] = (x-D) \cap D.](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5Bx%5D++%3D++%28x-D%29++%5Ccap++D.&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002)

prefer

Now we consider the expression

Clearly, this expression counts triples with

with ![a \in D[x]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=a+%5Cin+D%5Bx%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![a \in D[y].](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=a+%5Cin+D%5By%5D.&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) Since each a participates in

Since each a participates in  sums, the expression clearly adds to

sums, the expression clearly adds to  Now again we uniformize assuming the entire sum comes from terms of size

Now again we uniformize assuming the entire sum comes from terms of size  Thus there are

Thus there are  many pairs

many pairs  so that

so that ![D[x] \cap D[y]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5Bx%5D+%5Ccap+D%5By%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) has size

has size

What does this mean?

If is in both

is in both ![D[x]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5Bx%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![D[y],](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5By%5D%2C&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) we have

we have

thus

thus  and this happens in

and this happens in  different ways.

different ways.

Thus we have pairs

pairs  with

with  differences.

differences.

Applying Cauchy Schwarz, we get additive quadruples in

additive quadruples in

Applying the fact that each element of has

has  representations as pairs in

representations as pairs in  we get

we get  additive octuples in

additive octuples in  Since we have no more than

Since we have no more than  this tells us that

this tells us that  On the other hand, we know

On the other hand, we know

If which is ,for instance, true in the case

which is ,for instance, true in the case

then we're done. The sets

then we're done. The sets ![D[x]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5Bx%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) have

have To be precise, we find a typical

To be precise, we find a typical ![D[x]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D%5Bx%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to be almost invariant under

to be almost invariant under  distinct shifts and therefore to be almost additively closed.

distinct shifts and therefore to be almost additively closed.

to essentially belong to disjoint blocks of size

What if is much smaller than

is much smaller than  ? Then we ask how many differences

? Then we ask how many differences  do we have with

do we have with  representations. It is at most

representations. It is at most  since any more would imply too many additive quadruples in D. On the other hand, assuming that

since any more would imply too many additive quadruples in D. On the other hand, assuming that  pairs

pairs  have fewer than

have fewer than  differences would imply more than

differences would imply more than  octuples in

octuples in  again a contradiction. Thus we have exactly

again a contradiction. Thus we have exactly  such differences which means we can replace

such differences which means we can replace  by

by  which is smaller. We iterate until

which is smaller. We iterate until  stabilizes.

stabilizes.

However, it is not at all clear to me how this structure helps us. The easy Plancherel bound tells us no more than in a space of dimension

in a space of dimension  which doesn't say much about additively closed sets of size

which doesn't say much about additively closed sets of size  in the spectrum. If

in the spectrum. If  is really close to