The short answer if you don’t feel like reading a post with some actual mathematics in it is that I don’t know.

Now for the longer answer. A subset of

is called a Sidon set if the only solutions of the equation

with

are the trivial ones with

and

or

and

. Since the number of pairs

with

is

and

whenever

, it is trivial that if

is a Sidon set, then

, which gives an upper bound for

of around

.

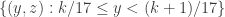

There is also a matching lower bound, up to a constant. I think it is due to ErdŎs. One notes first that the subset of

defined by

is a Sidon set inside

. Indeed, if

, then

and

. Assuming the quadruple is not degenerate,

, so we can divide the first equation by the second to deduce that

, and that implies that

and

, so the quadruple is degenerate for a different reason.

Thus, we can find a Sidon subset of of size

, which is the square root of the size of

. We can now regard this set as a subset of

, and then map each point

to the number

. It is easy to check that the resulting set is a Sidon subset of

.

Much more is known about this: the correct bound is now known up to a constant. However, that is not the theme of this post. What I want to discuss is whether any kind of converse of this result is true. That is, can one say that a Sidon set of size close to must be constructed in some kind of quadratic way?

Some very weak evidence in favour of a conclusion like that is that random methods fail miserably to produce Sidon sets of anything like size . Indeed, let’s pick a subset

of

randomly by choosing each element with probability

. The total number of quadruples

with

taken from

is roughly

(since apart from a few edge effects

and

can be chosen more or less freely and they determine

), and each nondegenerate one has a probability

. So the expected number of nondegenerate quadruples

with

is roughly

. For this to be smaller than

(so we can remove a point from each one and still have plenty of

left), we need

to be significantly smaller than

, which gives a bound of

, which gives us

.

There are several other ways to see that random sets of size are very different indeed from Sidon sets, which suggests that Sidon sets of size close to

must have interesting structure. But what is that structure?

It isn’t easy even to state a conjecture here, since before we map the subset of to the integers, we can apply an invertible linear transformation to it. It is hard to think of a way of characterizing the kinds of sets that can arise like this, let alone thinking about how to make the structure looser when the set has size only

. (Additive combinatorialists will immediately recognise that I am inspired by Freiman’s theorem here.)

But today … make that yesterday as a night has passed since I wrote those two words … I was at a talk given by Javier Cilleruelo, thanks to which I learnt of an example that places a much more serious constraint on any conjecture one might hope to make. The example is one I sort of knew already, since it is based on a brilliant argument of Imre Ruzsa, who created an infinite Sidon set such that the asymptotic size of

is around

. (As with the finite case,

is very easy; the true answer is conjectured to be

; Ruzsa was the first person to beat

and his exponent has not been improved.) What Cilleruelo mentioned in passing was that you can use some of Ruzsa’s ideas in an easy way to get a pretty decent example in the finite case. This is something I hadn’t realized. I presume Ruzsa himself was well aware of it, but I don’t remember it being mentioned in his paper (though I haven’t looked at the paper for many years, so he might have done). What I find particularly interesting is that the example is completely different from the graph-of-

type examples.

Since the construction is simple (to understand, that is) and rather gorgeous, I thought it merited a blog post. And maybe it can also serve as an advertisement for Ruzsa’s amazing paper.

It begins with the observation that the logarithms of the primes form a Sidon set of reals: if are primes with

, then either

and

or

and

; therefore, the same is true if

.

“So what?” it is tempting to say. After all, the logs of the primes are not integers. Indeed, there are far more of them than there are integers.

However, at this point a principle comes in that I often feel doesn’t deserve to be as incredibly fundamentally useful as it in fact is: that two distinct integers must differ by at least 1. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say, for example, that to prove that a concrete number is irrational or transcendental you have to find some way of reducing the problem to this principle. (That is, you say that if your number is rational/algebraic then there must be two distinct integers that have difference less than 1.) For this problem we make a much simpler use of the principle. If , then

, since

are integers. Since the derivative of

is

, that tells us that

and

differ by at least

. (One could be a bit more careful here: I think Cilleruelo stated a bound of

.)

Note what we now have that’s better: instead of merely knowing that in nondegenerate cases, we have a lower bound on the difference. This allows us to approximate and discretize.

So let’s start with all the logs of the primes up to , of which there are about

by the prime number theorem. If we multiply those by say

, then all the differences between the distinct sums, which were previously at least

, are now at least

. Therefore, if we move each number to the nearest integer, the differences will be altered by at most 2, so will be at least 1. So we have a Sidon set! It is a subset of the integers up to

and it has size around

, so this construction gives a Sidon subset of

of size around

.

The moral of this is that to prove a structural result about Sidon sets of density close to , then one would probably have to insist on close meaning “within a constant of” (which one would then relax to some slow-growing function later). Or alternatively, one would look for a much more general notion of structure, but I don’t see an obvious generalization of the two examples I now know. Another moral is that it’s worth looking for more examples of dense Sidon sets before even trying to make a conjecture.

July 13, 2012 at 5:05 pm |

Tim, Do you believe that every sidon set with t>0 already has structure? A second question: maybe easier than structure would be an upper bound on the number of sidon sets of the required size?

t>0 already has structure? A second question: maybe easier than structure would be an upper bound on the number of sidon sets of the required size?

July 13, 2012 at 11:22 pm

A recent result of David Conlon’s and mine gives at least something in this kind of direction. We show that if G is an Abelian group of order n and A is a random subset of G of size , then with high probability every Freiman homomorphism from A to another Abelian group extends to a Freiman homomorphism on G. This is completely untrue for Sidon sets, since then every map is a Freiman homomorphism. However, the property that all Freiman homomorphisms extend is much stronger than the property of not being Sidon, so the bound you can get this way on the number of Sidon sets is almost certainly far too weak. I imagine that as with other problems of this kind the number of Sidon sets is roughly comparable to the number of subsets of a single maximal Sidon set — that is,

, then with high probability every Freiman homomorphism from A to another Abelian group extends to a Freiman homomorphism on G. This is completely untrue for Sidon sets, since then every map is a Freiman homomorphism. However, the property that all Freiman homomorphisms extend is much stronger than the property of not being Sidon, so the bound you can get this way on the number of Sidon sets is almost certainly far too weak. I imagine that as with other problems of this kind the number of Sidon sets is roughly comparable to the number of subsets of a single maximal Sidon set — that is,  . I don’t even have a guess if you try to count Sidon sets of size

. I don’t even have a guess if you try to count Sidon sets of size  for

for  (but I haven’t thought about it, so maybe it’s easy to come up with a sensible conjecture).

(but I haven’t thought about it, so maybe it’s easy to come up with a sensible conjecture).

July 16, 2012 at 1:01 am

Dear Tim and Gil,

Another result in this direction was obtained recently by Kohayakawa, Lee, Rodl and Samotij (see Theorem 2.1):

Click to access Sidon.pdf

I think they also get some structural information about a ‘typical’ (in a weak sense) Sidon set of a given size, but it sounds like you’re hoping for something much stronger…

July 16, 2012 at 9:10 am

I took a look at some old data on Sidon sets which I had on my laptop, I once had a long wait in an airport which led to some simple computer experiments with Sidon sets, and from those data it looks like c is 4.1… in the estimate for the number of Sidon sets.

However this is data from what my laptop could do at the time so they are only for n up to 44, for general Sidon sets.

July 13, 2012 at 5:17 pm |

A characterisation of dense Sidon sets may also lead to progress on another intractable Erdos problem, namely to determine if there is an additive basis A of the natural numbers of order 2 (i.e. A+A=N) with bounded multiplicity function r_2 (i.e. every natural number is expressible as the sum of two elements of A in a bounded number of ways).

Note though that if we relax the Sidon property to that of having multiplicity that grows at most logarithmically, then random examples start working again thanks to Chernoff. This already rules out a lot of analytical techniques (e.g. Fourier analysis), as they have a hard time distinguishing between multiplicity 1 and logarithmic multiplicity. I’m not sure what that leaves one with; algebraic methods such as the polynomial method are a remote possibility, but I haven’t seen them used for inverse sumset problems before, only for direct sumset inequalities.

July 14, 2012 at 5:42 am |

This is vaguely reminiscent of the some theorems and conjectures loosely attached to the name “inverse sieve.” One assertion of this form states roughly that if![A \subset [N]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=A+%5Csubset+%5BN%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) such that

such that  has size near

has size near  and misses a constant fraction of the residue classes mod

and misses a constant fraction of the residue classes mod  for small

for small  then

then  is contained in the image of a quadratic polynomial. Helfgott and Venkatesh have some results in this direction. With this in mind, one might try to prove that a large Sidon set (or some appropriate subset and transformations thereof) must be ill-distributed mod

is contained in the image of a quadratic polynomial. Helfgott and Venkatesh have some results in this direction. With this in mind, one might try to prove that a large Sidon set (or some appropriate subset and transformations thereof) must be ill-distributed mod  for small

for small  . I have no intuition suggesting if this is plausible.

. I have no intuition suggesting if this is plausible.

July 16, 2012 at 9:17 am

One of my old programs looked for Sidon sets such that every initial segment is as balanced as possible mod p, no residue classes differing by more than 1.

There are of course fewer such sets but their sizes seem to grow at a rate comparable with that of general Sidon sets, perhaps smaller by some p-dependent factor. The same looks plausible when one uses several prime at the same time.

Here are two examples which are balanced mod 2, 3, and 5

{1, 8, 15, 34, 42, 53, 65, 96, 109, 112, 113, 114}

{1, 8, 15, 24, 47, 64, 66, 77, 85, 88, 113, 114}

July 20, 2012 at 8:54 am

Mark, this is an interesting idea, and I like this conjecture of Helfgott and Venkatesh very much. However I suspect that *very* dense Sidon sets, of size really close to the maximum of $\sqrt{N}$, are rather well-distributed in residue classes to small moduli.

See

Click to access 9808061.pdf

July 15, 2012 at 11:11 pm |

Hmm, I’ve just realized something that has a big influence on any conjecture one might wish to make, even in the case of sets of size . If you have a Sidon subset of

. If you have a Sidon subset of  of that size, then you can create a Sidon subset of, say,

of that size, then you can create a Sidon subset of, say,  by multiplying every element of your original set by 5 and arbitrarily adding 0, 1 or -1 to it. So there’s no hope of quadratic structure: the best one can hope for is a set that can be approximated by something quadratic. (Of course, then there are other things one can do like multiplying one of these perturbed examples by some appropriate

by multiplying every element of your original set by 5 and arbitrarily adding 0, 1 or -1 to it. So there’s no hope of quadratic structure: the best one can hope for is a set that can be approximated by something quadratic. (Of course, then there are other things one can do like multiplying one of these perturbed examples by some appropriate  mod

mod  , so things get even worse.)

, so things get even worse.)

July 16, 2012 at 9:39 am

Looking at the data for n=44 the size distribution for all Sidon sets is unimodal, the most common size is 7 and the maximum is 9. Here is the list of {size, number of Sidon sets} pairs for n=44.

{{0, 1}, {1, 44}, {2, 946}, {3, 13 244}, {4, 129 360}, {5, 845 408},

{6, 3 157 104}, {7, 4 748 144}, {8, 1 462 854}, {9, 27 202}}

For larger n I only had data for restricted Sidon set, the ones which are well distributed mod p, but they show a similar distribution.

Again this is for very(!) small n, but it looks like as “close” to maximum size one might need to be close by something additive rather than a factor.

July 16, 2012 at 7:53 am |

1) I think the size of the Sidon set constructed is around in the penultimate paragraph.

in the penultimate paragraph.

Thanks — corrected now.

2) You can also construct quite nasty examples from iterating ,

,  and the floor functions. For example, you can start from the primes

and the floor functions. For example, you can start from the primes  and instead of

and instead of  I think one obtains a Sidon set of roughly the same density by considering

I think one obtains a Sidon set of roughly the same density by considering  . You could also take

. You could also take  where

where  is taken from a Sidon set of a completely different nature. I imagine one could repeat this process. It’s difficult to guess what kind of structure is preserved by repeated logarithms and floor functions…

is taken from a Sidon set of a completely different nature. I imagine one could repeat this process. It’s difficult to guess what kind of structure is preserved by repeated logarithms and floor functions…

July 16, 2012 at 10:52 am

Actually, what I wrote in 2) isn’t properly correct as it stands, but I see a similar problem with the example in the post. Namely, how can one guarantee that the set actually has size at least $m/\log m$? For many different $p\leq m$ are such that the integer part of $\log p$ are the same. Surely one needs the primes to be spaced at least some multiplicative constant apart, whence one only gets a set of size around $\log m$?

July 16, 2012 at 3:43 pm |

Erdos and Turan originally showed $n^{1/2} + O(n^{1/4})$ as an upper bound. Lindstrom gave a beautiful really short proof of an upper bound of $n^{1/2} + n^{1/4} +1$, which looks like it is really loose, and could be tightened, but it’s deceptive.

IErdos offered $500 for a proof of an upper bound of $n^{1/2} + O(1)$.

July 20, 2012 at 8:58 am

Indeed, it seems very hard to improve Lindstrom’s result in any way. Erdos conjecture is surely false, as most likely one can dilate a Sidon subset of Z/qZ of size q^{1/2} so as to have a gap of size q^{1/2}logloglog q (say), and then “unwrap” so as to get a Sidon set of size q^{1/2} in an interval of length appreciably smaller than q. However, I have no idea how to achieve this with any of the known constructions of large Sidon sets modulo q. Being able to find such large gaps is most likely a generic property (i.e. has nothing to do with being Sidon) but I have no idea how to prove that either.

July 21, 2012 at 6:05 am

As a point of history, the Erdos-Turan proof and the Lindstrom proof both give (iirc, the “+1” can be improved to “+1/2”), although E-T only noted

(iirc, the “+1” can be improved to “+1/2”), although E-T only noted  .

.

January 12, 2013 at 11:19 am

I wonder whether one can use Ben’s idea in conjunction with Ruzsa’s

construction, as follows. Let $p$ be a prime, and consider indices (discrete

logarithms) with respect to a fixed primitive root modulo $p$. With every

integer $x\in[1,p-1]$ associate the residue class of $(p-1)x+p\,{\rm

ind}\,(x)$ modulo $p(p-1)$. The set of all $p-1$ resulting elements of

${\mathbb Z}_{p(p-1)}$ is a Sidon set. Define $\varphi\colon

[1,p-1]\to{\mathbb Z}_{p-1}$ by $\varphi(x)=x+{\rm ind}\, x\pmod {p-1}$.

Writing $(p-1)x+p\,{\rm ind}\,(x)=(x+{\rm ind}\,(x))p -x$, we see that to

answer Erdos’ question, it suffices to show that the full image

$\varphi([1,p-1])$ misses some, say, $\log\log\log p$ consecutive elements of

${\mathbb Z}_{p-1}$. A simple heuristic shows that is most certainly true (a

typical element of ${\mathbb Z}_{p-1}$ is missing in $\varphi([1,p-1])$ with

probability about $1/e$), but is there a hope to \emph{prove} this? Notice

also that we do not need to have the result for all pairs $(p,g)$ (where $g$

is a primitive root modulo $p$), but just for any infinite sequence of such

pairs.

January 13, 2013 at 8:38 am

(This comment is identical to that I posted yesterday, but with a proper formatting attempted.)

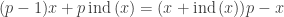

I wonder whether one can use Ben’s idea in conjunction with Ruzsa’s construction, as follows. Let be a prime, and consider indices (discrete logarithms) with respect to a fixed primitive root modulo

be a prime, and consider indices (discrete logarithms) with respect to a fixed primitive root modulo  . With every integer

. With every integer ![x\in[1,p-1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=x%5Cin%5B1%2Cp-1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) associate the residue class of

associate the residue class of  modulo

modulo  . The set of all

. The set of all  resulting elements of

resulting elements of  is a Sidon set. Define

is a Sidon set. Define ![\varphi\colon [1,p-1]\to{\mathbb Z}_{p-1}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cvarphi%5Ccolon+%5B1%2Cp-1%5D%5Cto%7B%5Cmathbb+Z%7D_%7Bp-1%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) by

by  . Writing

. Writing  , we see that to answer Erdos’ question, it suffices to show that the full image

, we see that to answer Erdos’ question, it suffices to show that the full image ![\varphi([1,p-1])](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cvarphi%28%5B1%2Cp-1%5D%29&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) misses some, say,

misses some, say,  consecutive elements of

consecutive elements of  . A simple heuristic shows that is most certainly true (a typical element of

. A simple heuristic shows that is most certainly true (a typical element of  is missing in

is missing in ![\varphi([1,p-1])](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cvarphi%28%5B1%2Cp-1%5D%29&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) with probability about

with probability about  ), but is there a hope to prove this? Notice also that we do not need to have the result for all pairs

), but is there a hope to prove this? Notice also that we do not need to have the result for all pairs  (where

(where  is a primitive root modulo

is a primitive root modulo  ), but just for any infinite sequence of such pairs.

), but just for any infinite sequence of such pairs.

July 17, 2012 at 8:24 am |

“the logs of the primes are not integers. Indeed, there are far more of them than there are integers.” Not quite right. There are exactly the same number of integers and logs of primes. I suspect that the ‘them’ is meant to refer to reals. 🙂

July 18, 2012 at 8:29 am

What Tim Gowers meant is that in a given interval [0,N], there are far more logs of prime than integer.

July 19, 2012 at 5:53 am

Ah, I see! But the discussion at that point was about infinite Sidon sets, so I was distracted. Thanks, Benoît.

July 20, 2012 at 8:46 am |

Tim, I think there are constructions of Sidon subsets of $\{1,…,N\}$ of size about $\sqrt{N}$ coming from finite fields, due to Bose and Chowla. Consider $F_p$ inside $F_{p^2}$, and let $a$ be a generator of the multiplicative group of $F_{p^2}$. Let $S \subseteq Z/(p^2 – 1)Z$ be the set of all $s$ such that $a^s – a \in F_p$. Then this is a Sidon set (in fact it is Sidon modulo $p^2 – 1$). Ruzsa has some other constructions too. I certainly believe that all large Sidon sets are “algebraic” in some way that I am unable to make precise. This example of Ruzsa shows that one cannot hope for too much in that direction. I must say that I wasn’t previously aware of it either, despite having read Ruzsa’s paper in detail some years ago.

July 21, 2012 at 5:21 am

FYI, the constructions of Bose & Chowla (mod ), Singer (mod

), Singer (mod  ), and Ruzsa (mod

), and Ruzsa (mod  ) are given in my now old survey/bibliography at Electronic Journal of Combinatorics (http://www.combinatorics.org/ojs/index.php/eljc/article/view/ds11).

) are given in my now old survey/bibliography at Electronic Journal of Combinatorics (http://www.combinatorics.org/ojs/index.php/eljc/article/view/ds11).

July 21, 2012 at 6:03 am |

There’s an idea I’ve been sitting on for years, and haven’t been able to turn it into anything. First let me give a dubious heuristic-y construction of a Sidon set, and then I’ll give an actual example to demonstrate that, at least, the idea isn’t idiotic.

Let be a dynamical system, and suppose that

be a dynamical system, and suppose that  is ergodic, and that

is ergodic, and that  . Let

. Let  be an arbitrary set (measurable, of course), and let

be an arbitrary set (measurable, of course), and let  be a randomly chosen point of

be a randomly chosen point of  . Now let

. Now let  be the set of integers

be the set of integers  where

where  is parameter to be named later. Since

is parameter to be named later. Since  is ergodic, the expected size of

is ergodic, the expected size of  is

is  ; perhaps we can take

; perhaps we can take  so that

so that  . I claim that

. I claim that  is pressured to be a Sidon set, at least after removing a small number of elements.

is pressured to be a Sidon set, at least after removing a small number of elements.

Why? Suppose that are all in

are all in  , and

, and  , contrary to the claimed Sidon-ness of

, contrary to the claimed Sidon-ness of  (set

(set  ). This means that the two points

). This means that the two points  ,

,  are both in

are both in  , and so are “close together”. But also

, and so are “close together”. But also  maps these two close points to

maps these two close points to  ,

,  , which are not only close to each other but close to the original two points. My intuition is that if

, which are not only close to each other but close to the original two points. My intuition is that if  is sufficiently strongly mixing, then it should be very rare (i.e., very few

is sufficiently strongly mixing, then it should be very rare (i.e., very few  ) that a small power of

) that a small power of  maps two points in

maps two points in  to two points in

to two points in  . Caveat: I don’t know what “sufficiently strongly mixing”, “very rare”, or “small power” actually need to mean to make this work, if indeed there is any way to make it work.

. Caveat: I don’t know what “sufficiently strongly mixing”, “very rare”, or “small power” actually need to mean to make this work, if indeed there is any way to make it work.

So here’s the promised example, which is really a Bose-Chowla set in disguise. Let ,

,  Lebesgue measure, and define

Lebesgue measure, and define  to be

to be  . This is a linear map with determinant 6, so it is ergodic. Set

. This is a linear map with determinant 6, so it is ergodic. Set  , and let

, and let  be any of the sets

be any of the sets  with

with  (or replace the special role played by

(or replace the special role played by  with

with  , that works, too). Let

, that works, too). Let  . (Above, I suggested taking random

. (Above, I suggested taking random  and fixed

and fixed  , but here I'm taking one

, but here I'm taking one  and many

and many  's. Oh well.) All 32 of the resulting sets are Sidon sets!

's. Oh well.) All 32 of the resulting sets are Sidon sets!

All of the constructions of Sidon sets that give are based on finite fields, and the error term in the maximum possible size of a Sidon set are from the gaps between prime numbers. Any construction that gives

are based on finite fields, and the error term in the maximum possible size of a Sidon set are from the gaps between prime numbers. Any construction that gives  without using primes would be interesting, and possibly the first improvement since the early 1940s.

without using primes would be interesting, and possibly the first improvement since the early 1940s.

July 21, 2012 at 7:18 am |

Hi Dr Gowers

my name is Yan, I read “what is implied by “implies””you wrote

And I have a question for you. Can you just spend a little bit time and give me some help?

it is annoying question about vacuous proof.

for example, let’s prove ∅ is the subset of every set A.

This statement can be translated into another way:for every x, if x is the element of ∅,then x is the element of A.

since x is the element of ∅ is always false. So this statement is vacuous true.

My problem is why can‘t we substitue x by non-exist things,for example, what if x represents unicorn?then unicorn is an element of ∅ will be true not false?so x is the element of empty set is not always true

by this problem, can we get the conclusion that all the varibles in the statement can just be substituted by exist things? which means the scope of a variable can just be exist thing?

I appreciate your help Dr Gowers~

September 17, 2012 at 5:57 pm |

[…] What are dense Sidon subsets of {1,2,…,n} like? (gowers.wordpress.com) […]

November 18, 2017 at 4:29 pm |

If , we define $P_S=S_0 + S_1.X+….+S_n.X^n$.

, we define $P_S=S_0 + S_1.X+….+S_n.X^n$.

Maybe a conjecture could be of the form : , with

, with  , such that

, such that  there exists

there exists  , such that

, such that  ,

, is a fonction that we have to find , that is close to identity

is a fonction that we have to find , that is close to identity is a set of Sidon sets with some quadratic property that we have to precise

is a set of Sidon sets with some quadratic property that we have to precise is a increasing fonction from

is a increasing fonction from ![(\mathbb{Z}[X],<_X)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%28%5Cmathbb%7BZ%7D%5BX%5D%2C%3C_X%29&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) to

to  , where

, where  is order relations that we also have to precise (for example we can take

is order relations that we also have to precise (for example we can take  iff

iff  )

) is such that

is such that  is small when

is small when  is small.

is small.

For any Sidon set

Where

_

_

_

_

The idea is that if we get close to

close to  we can find a Sidon set with a quadratic structure close to

we can find a Sidon set with a quadratic structure close to  . But maybe it is not enough and you want

. But maybe it is not enough and you want  to have itself the "quadratic property", not just close to a set that has it….

to have itself the "quadratic property", not just close to a set that has it….

We can also state a "skeleton" of direct conjecture – that could maybe help to find/solve the inverse problem that we try to formulate – as :

For any , there exists

, there exists  such that

such that

where

where  is close to

is close to  when

when  is small (for

is small (for  )

) ,

,  ,

,  so I don't really "say something" neither. But just a direction, so that we might be able to discuss on the choice of each parameter.

so I don't really "say something" neither. But just a direction, so that we might be able to discuss on the choice of each parameter.

As I'm not familiar with the problem, I won't take the risk to give explicit

November 18, 2017 at 4:41 pm

I fisrt took from

from  and wrote the condition

and wrote the condition  , I think it was a better precaution, we just say that

, I think it was a better precaution, we just say that  is small when

is small when  is close to

is close to  instead of previous “

instead of previous “ is small when

is small when  “is small”.

“is small”.

November 23, 2017 at 7:21 pm

As Ben Green points out above, it is too much to ask for quadratic behaviour. For example, consider the subset of that consists of all points

that consists of all points  , where

, where  is a generator of the multiplicative group mod

is a generator of the multiplicative group mod  (which I have denoted by

(which I have denoted by  ). Then if

). Then if  , then we have

, then we have  such that

such that  , which gives us that

, which gives us that  , and therefore

, and therefore  and therefore

and therefore  . This example can be embedded into the integers in the usual way, and shows that it is possible for an example to be non-quadratic in a fairly fundamental way. So a good conjecture would somehow have to come up with a definition that could unify this example with the quadratic one. It seems quite a good idea to focus on graphs of functions: I think it may be possible to convert any example into a graph by a process such as multiplying by a random number mod

. This example can be embedded into the integers in the usual way, and shows that it is possible for an example to be non-quadratic in a fairly fundamental way. So a good conjecture would somehow have to come up with a definition that could unify this example with the quadratic one. It seems quite a good idea to focus on graphs of functions: I think it may be possible to convert any example into a graph by a process such as multiplying by a random number mod  , for some prime

, for some prime  close to

close to  , splitting up into intervals of length roughly

, splitting up into intervals of length roughly  , and throwing away a certain proportion of the set so that each element lives in the first half of its interval and there is only one such element per interval.

, and throwing away a certain proportion of the set so that each element lives in the first half of its interval and there is only one such element per interval.

December 12, 2018 at 8:58 pm |

[…] bound are not optimal and that the truth lies somewhere between and for any and . One can see this blog post of Gower’s and the comments within for interesting discussion of this […]

January 23, 2021 at 4:21 am |

[…] refer the interested reader to this consult this nice survey of O’Bryant and this beautiful blog post of Gowers for more […]

July 14, 2021 at 2:34 pm |

[…] “What are dense Sidon sets of {1, …, n} like?”, asked Tim Gowers on his blog almost ten years ago. A Sidon set is a set without any solutions to , which in additive combinatorics jargon means that it has minimal additive structure. Almost paradoxically, large sets with this property appear to be structured in another way, and that’s a bit of a mystery currently. […]